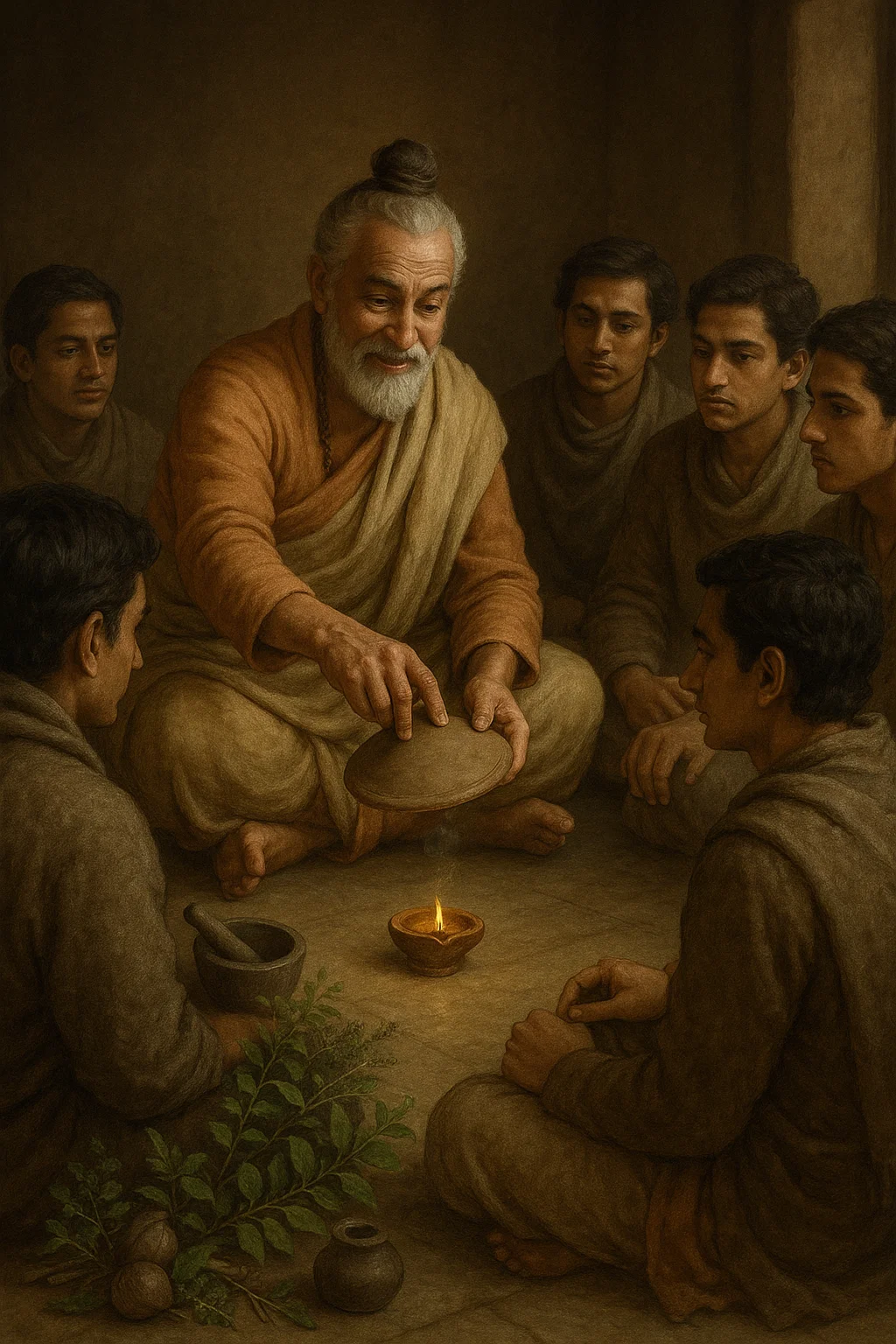

It is Śiśira, the season of cold and dry weather. The morning sun is pale, and a cold wind moves through the dry branches. Smoke rises from village houses, where fires burn through the long nights. Inside the āśrama hall, the wooden shutters are drawn, and in the corner, a fire burns steadily. The students sit close together in their cotton shawls, listening as Ācārya Charaka begins his teaching.

[One by one, patients enter, all recovering from illnesses shaped by the season.]

Case 1: The farmer with digestive recovery

[A lean farmer bows and speaks.]

Farmer: A month ago, I felt heavy even after small meals. Hunger had faded, and belching carried the taste of half-digested food. My stool was not well formed. After following your advice, now my hunger has returned, digestion feels light, and my stool is well formed.

Charaka (to the students): You remember, he had reported heaviness, bloating, loss of hunger, and stools that remained unprocessed. First, we gave him Dīpana to awaken the weakened fire. For this, we used Trikaṭu composed of Pippalī (long pepper), Śuṇṭhī (dry ginger), and Marica (black pepper). These herbs reduce heaviness and intensify the fire. Next, we gave Citraka (Plumbago zeylanica), Ajamodā (Trachyspermum ammi), and Musta to achieve Pācana, so that the undigested Āma could be digested and cleared.

Aaruni: But what is Āma?

Charaka: When the fire is weak, the food remains unprocessed and untransformed. This untransformed food is called Āma.

Aaruni: So these herbs did all the work!

Charaka: No! Apart from these herbs something else was also corrected. What is that?

Dhanvan: I remember that you also corrected his meal timings and asked him to rest after food. You asked him to eat only when he was hungry, not to eat too much, and not to fast too much. You asked him to eat food when it is still hot, not to engage in arguments while eating, not to laugh too much while eating and to focus on what is being eaten.

Charaka: Yes. I advised these measures because something deeper had to be corrected. Listen: his hunger had not completely vanished. The fire, Agni, though weak, was still there. Yet transformation did not follow. Why?

Dhanvan: Perhaps because the fire wasn’t intense enough?

[Charaka takes them to the kitchen nearby and points to the cooking fire. An attendant uses a dry, hollow bamboo shoot to puff air into the flame while also stirring the pot once in a while using a wooden spoon.]

Charaka: Well, observe rice gruel being cooked on the fire. How does the cook ensure that it cooks uniformly? How does he ensure that the fire burns not too intensely nor too mildly?

Devadatta: I can see the cook repeatedly moving the rice within the pot using a long wooden spoon.

Aaruni: I can see the cook using a piece of dry bamboo shoot to blow air when the fire is too mild to make it burn intensely.

Charaka: Good observations. In this farmer, the food was not being mixed and moved properly. The movement in the gut was too slow.

Aaruni: But how do we know that?

Charaka: His stomach felt heavy for too long. That is because of the slow movement.

Aaruni: What causes movement in the gut?

Dhanvan: Vayu! We have discussed that earlier. All movements are because of Vayu.

Charaka: True. When the cooking pot is left untouched, the rice grains that sink below soften first and stick to the bottom. They scorch if left unstirred for long. But when the spoon stirs the gruel again and again, the warmth reaches every part, and the whole mass becomes well-cooked and doesn’t stick.

Aaruni: So, the flames do not depend on wood alone?

Charaka: Fire needs wind to stir it along with wood. Can you see how the flame revives when air moves through bamboo steadily?

[He then takes a small lamp and covers it with a clay lid. After a few moments, thin smoke seeps from beneath the rim, and the light vanishes.]

Charaka: When no air enters the lid from outside, or when the smoke fills inside, the flame suffocates, even though oil and wick remain.

Aaruni: Just as the smoke that chokes us?

Charaka: Yes.

[He then uncovers the lamp, relights it, and turns to a student.]

Charaka: Now you, blow hard upon it.

[The student leans forward and blows strongly upon it. The flame flares briefly and is extinguished.]

Charaka: See, too forceful a wind also destroys the flame.

Devadatta: So both no-air and storm are harmful.

Charaka: Exactly. It is the measured, balanced air that sustains the fire. That is why we call it Samāna, the equal, the optimal. Within the body too, this central Vāyu neither destroys nor inflames. It moves just enough, mixing and churning, and separates the nourishing portion, rasa, from the waste, mala.

Aaruni: How was Samāna corrected in this farmer?

Charaka: Samāna Vāyu is steadied not by drugs alone but by rhythm. When meals are taken timely, in proper measure, only after the previous food is digested, and when the body rests after eating, the central motion finds its rhythm again. When Agni and Samāna work together, digestion follows.

Dhanvan: So this Samāna is like the steady breath through a dry hollow bamboo: measured, rhythmic, centrally guiding.

Charaka: Exactly. It is the bellows of the gut. It is not fire alone that brings change, but the steady activity of Samāna Vāyu. It mixes, churns, and carries the heat evenly. Without that central stirring, food is left half-cooked within.

Dhanvan: Does it mean that Samāna transforms what Prāṇa brought in and Apāna expels what remains?

Charaka: Well-said. Prāṇa Vāyu governs input and intake, ensuring that food and breath enter steadily, while Apāna governs the downward expulsion of wastes, and Samāna works between them, helping in transformation.

Case 2: The poet with recovering speech

[A young poet enters the hall, holding a palm-leaf manuscript in his hand. He speaks with some effort at the start, but once begun, the words flow smoothly.]

Poet: Master, when I first came, my speech was faulty. Words rose in thought, but at the tongue they stopped. At times a syllable repeated, at times the voice stopped altogether. As you instructed, I read aloud Mahābhārata each evening before my family. At first the stammer was strong, but with practice the sounds began to flow. Now my voice is steadier, and the tongue locks less often.

Charaka (to the students): His breath was sound, his throat clear, his mind sharp. Yet voice did not emerge. What held it back?

Aaruni: There was no obstruction in his throat, but the act of utterance failed.

Charaka: Just so. The thought was formed, the will to speak was present, but the rising motion was disturbed. This is Udāna Vāyu. When Udāna weakens, speech stops, confidence wanes, and expression remains bound within.

[Charaka takes up a conch. He lifts it to his lips, chest expanding. With a strong upward breath, a deep, resonant call fills the hall. Then he attempts again with weaker force; only a faint sound, broken and uneven, emerges.]

Charaka: See, the conch is clear within, yet unless the breath rises strongly upward, no sound comes. With full Udāna, the voice surges forth, filling the space. With faltering Udāna, effort is spent, but the sound dies at the lips.

Devadatta: How was Udāna corrected?

Charaka: By repeated practice. Recitation steadies Udāna, as exercise strengthens a limb. I asked him to read aloud verses from the Mahābhārata: slow at first, then in measured rhythm, day after day. Setting thought into sound, with breath controlled and confidence growing, the flow was restored. In this way Udāna regained its balance.

Case 3: The elderly man with pain in legs and cold limbs

[An elderly merchant approaches, walking steadily]

Merchant: Master, this season has tested me. When I approached you a fortnight ago, even small efforts brought pain in my legs. My limbs grew cold and numb, especially in the evenings, and I tired quickly. But now, with your guidance, I feel stronger. I walked a full yojana this morning without exhaustion, and warmth has returned to my hands and legs.

[Charaka places fingers on his wrist, then his palm on his chest, and nods.]

Charaka (to the students): You remember, though his heartbeat was steady, the pulse at his wrist was faint, and his limbs cold. He also had numbness in his legs and mild discoloration on the skin.

Dhanvan: What does that suggest?

Charaka: The center was active, but the flow of nutrition outward was weak. Rasa did not reach the periphery.

Dhanvan: What makes the Rasa flow? Another Vāyu?

Charaka: Just so. There is a Vāyu that resides within the heart, spreading nourishment to all directions. That is Vyāna.

[Charaka steps to a small metallic pipe resting on a shelf near the fire. He lifts it.]

Charaka: This pipe is used for dhūmapāna, the inhalation of medicated vapors, a therapy advised in certain throat disorders. Just yesterday, it was in use. A wick made by mixing powdered herbs with ghee was placed inside, and when gently lit, it released vapors that soothed the throat. But now, see what the cold has done: the residual ghee has solidified and sealed the passage.

[He warms the pipe gently over a nearby flame. The hardened ghee begins to melt, and a thread of smoke escapes from the mouth.]

Charaka: Nothing was blocking it. Yet the flow had ceased. Not from obstruction, but because of solidification caused by cold.

Devadatta: So Vyāna, too, can be stopped in this way by cold?

Charaka: Yes. The heart continues to beat, but Rasa fails to spread. The limbs grow cold, weak, and numb. When warmth is applied, the channels soften, open up, and Rasa begins to reach the periphery. As it flows into the distant parts, nourishment is restored, numbness recedes, and natural colour returns.

[He sets the pipe aside. A faint trail of smoke drifts upward.]

Aaruni: I remember. You had asked him to keep the surroundings warm by using fire, to avoid bathing in cold water, to wear warm clothes, and to sit under the warm sun.

Charaka (turning to the students): Precisely. Warmth facilitates movement of Rasa.

Dhanvan: Is distributing Rasa the only function of Vyāna?

Charaka: Vyāna not only distributes nourishment, but also governs movement throughout the body. The stride of walking, the lift of the arm, the throwing of a stone, even the blink of an eyelid are guided by Vyāna.

[The elderly merchant thanks Charaka, gratitude in his face, and leaves. The students warm their hands by the fire, thoughtful at the lesson.]

Discussion:

[Charaka gestures for his students to gather]

Charaka: Now, Aaruni, Dhanvan, what have these three cases shown us?

Aaruni: That movement within the body is not just inward and outward. There are three other forms: central, rising, and spreading.

Dhanvan: We call them Samāna, Udāna, and Vyāna. Each governs a distinct axis of life.

Charaka: Without Samāna, food does not get churned and hence remains inadequately digested. Without Udāna, thought forms but speech fails. Without Vyāna, the heart beats but limbs grow cold. Vāyu is not mere wind; it is the intelligence of digestion, expression, and distribution.

Aaruni: So what began as three patients now becomes patterns of internal dynamics?

Charaka: Yes. Theory begins with attention. Remember that Prāṇa Vāyu, which draws inward, and Apāna Vāyu, which governs downward expulsion, complete the picture. Together, these five Vāyus sustain the life. Let these Vāyus guide both your diagnoses and your understanding.

Aaruni: How were these Vāyus discovered?

Charaka: They were formulated in the effort to explain recurring patterns. First came attentive observation, then the grouping of symptoms, then the search for unifying principles. Only afterwards did our teachers assign names to these patterns. Remember this well, such constructs are not fixed truths or axioms. They are working models, to be refined as understanding deepens and new evidence emerges.

[The fire burns lower, and the students sit absorbed in thought.]

####

Leave a Reply