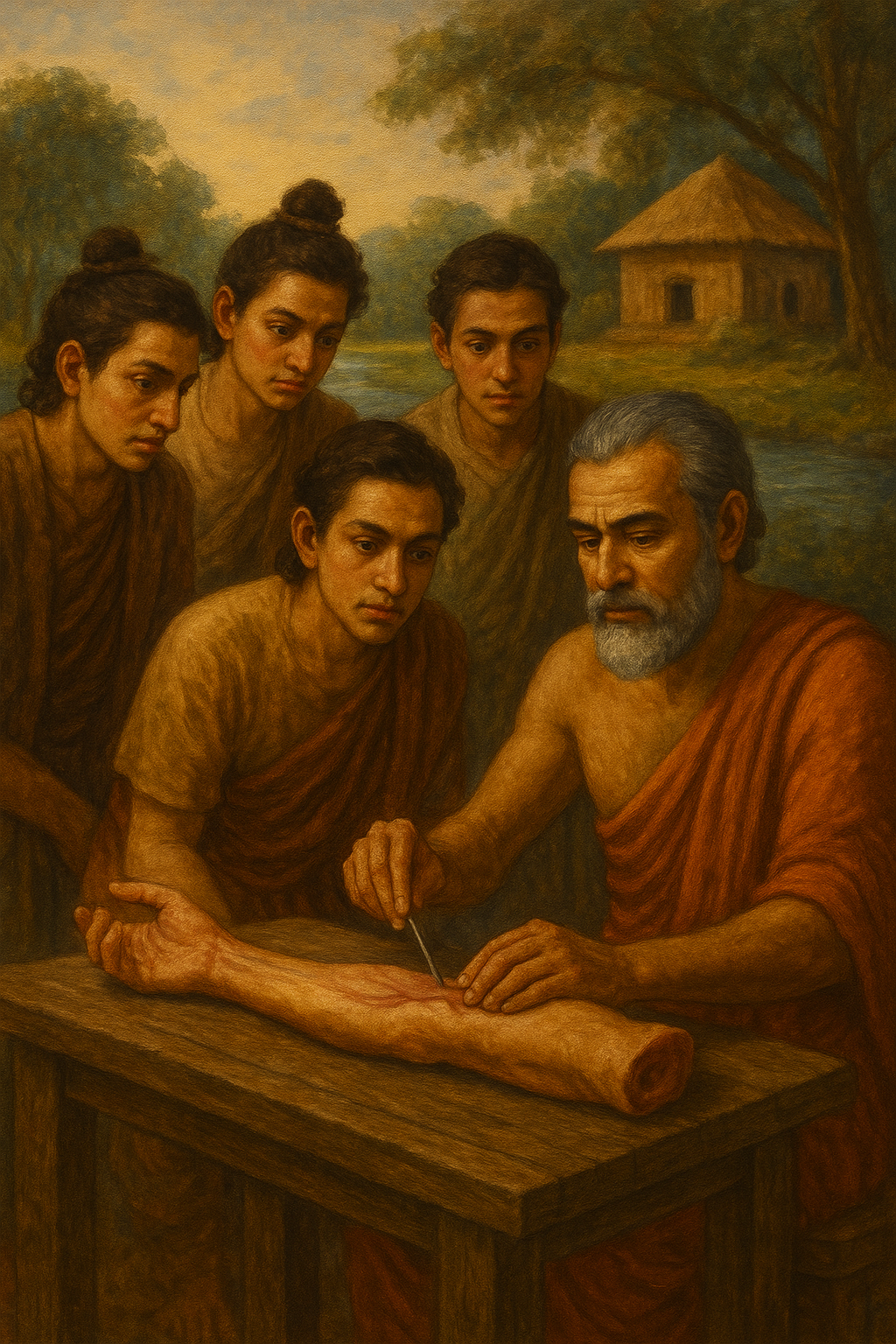

[A quiet grove on the banks of the Ganga. The morning air is cool and still. A group of pupils, Ruru, Ketana, and Ananda, are seated before Sushruta. Before them lies a cadaver, wrapped in Kusha grass, kept under a shallow stream of flowing water, carefully prepared for dissection in accordance with tradition.]

Sushruta (addressing the students): You have all memorised the names of the seven tissues, known as the seven dhātus: Rasa, Rakta, Māṃsa, Meda, Asthi, Majjā, and Śukra, many times. What do you know about them?

Ruru: Master, do we not also use the term Rasa to indicate taste?

Sushruta: Indeed, we do. The meaning depends on the context. Rasa signifies taste, it also denotes the first dhātu, and furthermore, as the Nāṭyaśāstra teaches, it refers to the aesthetic emotions depicted in classical dance and drama.

Ananda: Master, we understand that Rasa is the nourishing essence, the fluid formed after the complete digestion of food, which pervades the entire body. Rakta is the red-colored blood that sustains life. Māṃsa refers to the flesh that envelops the bones and joints, while Meda denotes the fatty tissue. Asthi are the bones that provide structural strength, and Majjā is the marrow that fills the bony cavities. Finally, Śukra is the tissue responsible for reproductive functions.

Sushruta: Yes. But today, let us inquire into why they are always named in this same sequence. Is it arbitrary? Is it in this sequence that they are arranged? Is it in this sequence that they are formed? Is it in this sequence that they are nourished? Is it in this sequence that they deplete? Is it in this sequence that their mobility varies? After all, what purpose does this sequence serve?

Ananda: But Acharya, may I ask, what is a dhātu in the first place? I am not sure of the definition.

Sushruta: A dhātu is that which supports and sustains the body, whether by structure or by function. Some dhātus like Māṃsa and Asthi, give form and strength, while others preserve vitality and continuity. Every organ in the body is composed of different dhātus. For example, the heart (hṛdaya) is primarily made of Māṃsa-peshi, muscle tissue.

Ananda: I can understand solid structures such as muscles and bones, supporting the body. But we have fluid dhātus like Rasa, Rakta, and Śukra. How do they support and sustain the body?

Sushruta: Well, when there is uncontrolled loss of fluids either in the form of bleeding, vomiting or purgation, life could be in danger. If there is no Śukra, one cannot produce offspring, and the line of life is broken. That too is sustenance in a broader sense.

Ruru: Master, I read that Rasa becomes Rakta, Rakta becomes Māṃsa, and so on. The earlier dhātu is converted into the next, like milk turning into curd, curd into butter, and butter into ghee. Some say this explains the sequence.

Sushruta: This view is confusing, though widespread. It is not conversion, but sequence, that is important. To emphasise the importance of the sequence – both temporal and spatial – scholars proposed the conversion theory. But have you asked yourself why is this sequence itself important?

Ruru: But you taught us that Rañjaka Agni transforms Rasa into Rakta?

Sushruta: Yes, that is the only instance where transformation takes place. In other cases it is not so. Let us see what is the importance of this sequence.

[He uncovers the forearm of the cadaver, exposing the skin.]

Sushruta: Let us begin with this part of the body. What is the outermost covering?

Ananda: That is the Tvak, Acharya, the skin.

Sushruta: Yes. This skin protects and preserves Rasa, the fluid essence that first arises from properly digested food. At the same time Rasa nourishes skin too. In cases of burns and scalds, Rasa is lost through damaged skin, and the condition could be life threatening. Skin is also an indicator of the sufficiency of Rasa. That is why we depend on the examination of Tvak, as we cannot directly examine Rasa.

Ruru: I think the other reason could be that sweating happens through skin and sweat in turn helps in regulating the fluid content within the body. Sweat also helps in regulating body heat. In fevers, when the body is hot, sweating helps to cool it down.

Sushruta: True. Physicians observe the skin for signs such as dryness, loss of smoothness, wrinkling, or swelling. From these changes they infer the state of fluids within the body. The skin, therefore, serves as a practical surface indicator from which inferences about internal fluid status can be drawn.

[He makes a small incision on the skin with a scalpel, showing the tissue layers beneath]

Sushruta: Now, though this is a lifeless body and shows no bleeding, tell me, what happens when the skin is cut in a living person? As in when an ear lobe is pierced?

Ruru: Blood emerges immediately, Acharya, even from a small cut.

Sushruta: Correct. Though large blood vessels lie deeper, Rakta pervades even the superficial tissues including skin through fine vessels. Thus, we understand that Rakta lies just beneath the Tvak.

Ananda: Can we separate out Rasa from Rakta, since both are fluids? And when burns and scalds happen why does only Rasa emerge?

Sushruta: The skin protects Rasa. When fire harms the skin, Rasa seeps out and gathers as clear fluid in blisters. But when the burn penetrates more deeply, the inner tissue, Rakta, also can be damaged. Thus we learn that Rasa is held at the surface, while Rakta lies deeper within.

Ananda: That makes things clear.

Sushruta: In deeper tissues, the nutrient fluid Rasa cannot be separated from Rakta. Rasa and Rakta move together in the same tubular structures. But their functions differ. A loss of Rakta produces pallor and weakness, whereas a loss of Rasa produces dryness and thirst- the signs of fluid loss. In Pandu, pallor, the person becomes weak and pale. We have seen this in Potter’s case. Remember?

Ketana: Yes, Master. Very well.

Sushruta: Then there lies Māṃsa when you go deeper. See here. (Shows the muscle underneath)

Ananda: But I can see a thin whitish layer here. Is it Medas, the fat?

Sushruta: Yes, it is. But we will consider it after Māṃsa.

Ananda: I have a doubt here, Master. We often see fat, Meda, just beneath the skin, especially in the abdomen and buttocks. Often in the obese this is the rule. Even in the forearm, here, we see a thin layer of Meda. Why then is Māṃsa placed before Meda in the dhātu -sequence?

Sushruta: An excellent observation. Muscles are firm, active, and responsible for movement. Meda, fat, on the other hand, is soft and supportive but inactive. In comparison to Rasa, the freely flowing fluid, Rakta is slightly denser, but it flows too. Māṃsa is firm but that too provides movement. From the earlier to the later dhātus, mobility diminishes. Do you notice this? Hence Meda is placed after Māṃsa.

Ananda: Is gradual reduction in mobility one reason behind this sequence?

Sushruta: Yes! Though Meda may lie above muscle in certain areas, it is also located between the muscle groups as intermuscular fat, Vasā. I agree, here there is some mismatch with respect to spatial arrangement. But we consider Meda after Māṃsa because in a starving, cachectic person, building muscles is easier with good nutrition such as meat soups, but fat takes time to form.

Ketana: I think here comes the sequence of replenishment! Am I correct?

Sushruta: Yes, but we will concentrate on the anatomical, also called spatial, arrangement now. We will take up the matter of sequential depletion and replenishment in the afternoon hours.

Ketana: But let me ask this: when there is conflict between spatial arrangement and temporal replenishment, we adjust our sequence to what is clinically most relevant. Is my understanding correct?

Sushruta: Very sharp observation, Ketana! Yes, that is how theories are adjusted when the observations themselves are in conflict. Ultimately what is more important for a physician? It is the success in treating the living, not their understanding of the cadavers! And that is why it is wise to place Meda after Māṃsa in the sequence because of its clinical relevance.

Ruru: That is certainly convincing. I think Asthi is situated even deeper. Hence it comes next. Is that correct?

Sushruta (getting deeper and exposing a bone): Yes. As we go deeper, we encounter bones, which are hard and rigid. Their movement entirely depends on Māṃsa, muscles. They cannot move independently. And within them lies Majjā, marrow, located in the hollow spaces. It is clear that Majjā cannot be formed unless Asthi is first present.

Ruru: We do not see Śukra here. Where does it reside?

Sushruta: You see rightly. Śukra is not evident in this cadaver, for it becomes manifest only in the living. It manifests only in the youthful years. That is why it is placed last in the sequence. Its movement is evident only intermittently, only during copulation. It is the seminal fluid in men. Śukra in women is something we will take up later. Bones and joints move when muscles move, but movement of Śukra is lesser than even bones and marrow.

[He steps back and addresses them]

Sushruta: Therefore, let no one say that one dhātu turns into another. That view leads to confusion. Instead, remember: one of the reasons why this sequence was conceptualised is their arrangement inside the body, especially in the limbs.

Ketana: I get that. In the abdomen and thorax, this arrangement is applicable only partially for there are different organs inside. Is that correct?

Sushruta: Yes. Another reason is the gradual decrease in their mobility. However, there are other reasons as well: the sequence of formation, sequence of depletion, and sequence of replenishment. We will discuss this after we see some patients waiting outside.

####

[The lesson continues in the afternoon hours. The students sit attentively, their minds focused.]

Sushruta (to his pupils): You have now understood how dhātus appear in the body and how their mobility varies. Let us now consider how the body is formed in the womb. This knowledge comes from careful study by our teachers, who examined naturally expelled foetuses in accordance with ethical principles.

Ananda: Ethical principles?

Sushruta: Yes. Foetuses must not be deliberately aborted for study. Only those that are naturally expelled may be examined, and always with consent of the parents and with reverence. But we shall keep that matter for another occasion. Now attend closely to what physicians have observed: in the earliest stages, the Garbha, the embryo, is fluid and formless. One cannot distinguish limbs or organs. This is the stage of Rasa, sustained by the Rasa received from the mother through the umbilical cord.

Ananda: So it is the mother’s Rasa that nourishes an embryo!

Sushruta: Yes! Soon after, the Garbha becomes reddish and begins to show the first signs of life. This redness is the sign of Rakta. The teachings say that the function of Rakta is to give jīvana, life itself, thus it is formed early.

Ananda: Acharya, when does Māṃsa take form?

Sushruta: Māṃsa begins to appear as the body acquires mass, as the limbs, the back, the abdomen acquire volume. This occurs after Rakta, and embryo takes somewhat stable shape because of Māṃsa. Without muscle, the limbs cannot act, nor can the heart beat with strength. Hence Māṃsa is the third dhātu.

Ketana: Next is Meda, I guess?

Sushruta: Yes, it is formed after Māṃsa in sequence. It arises after the formation of muscle because it has to provide a covering layer around the muscles. Further, it gives only plumpness to the foetus, not strength. Only then Asthi, bones, form.

Ketana: This explanation somehow doesn’t convince me. Muscles must be attached to bones so that movement around the joints can happen. To do that, bones must be present before muscles are formed. Am I wrong here?

Sushruta: An excellent point, Ketana. Indeed, muscles must eventually attach to bones to allow for movement at joints. But we must consider how the body first develops, not just how it works when complete. In the early Garbha (embryo), there is no movement at joints because neither bones nor joints are yet formed.

Ruru: As you suggested in the beginning, the Garbha is liquid first, soft afterwards, and firm only when it is mature.

Sushruta: Yes, the harder forms such as limb bones, skull, and spine begin to appear only later. In the early weeks of pregnancy, the embryo is too soft. It starts to get harder only in the later months.

Ruru: Majjā, marrow, must then come after the bones, for bones contain Majjā within their cavities.

Sushruta: Exactly. Majjā is never seen without Asthi.

Ananda: And Śukra?

Sushruta: You will not find it in the womb. We have observed that Śukra does not manifest until the body reaches maturity. It remains unexpressed until the adolescent years. Therefore, it is the last in manifestation.

Ananda: So, it is wrong to say that Śukra is first formed in Majjā and then is oozed out of bones to spread all over. Right?

Sushruta: Yes. Śukra is formed in the testicles, not in Majjā.

Ananda: How do we know that?

Sushruta: When you castrate a bull, it loses its ability to reproduce. Thus a broad order similar to the cadaveric arrangement appears during development. This is not mere imagination; it is drawn from careful observation.

####

[Sushruta now shifts from anatomical and embryological insights to practical medicine. He now discusses how the sequence of dhātus determines disease progression and the strategy of treatment.]

Sushruta (addressing his pupils): We have seen the sequence of dhātus as evident in structural arrangement, gradual decrease in mobility and the sequence of their development in the womb. But this order is no less important in treatment. Consider a person who has been starving for many days and has only had small quantities of water to drink, perhaps because of drought-driven food scarcity. Let us imagine what happens.

Ruru: Drought? I think the person would like to drink water first.

Sushruta: That is correct. First there will be a depletion of Rasa, Rasa kṣaya, the symptoms of fluid loss in the body. The mouth becomes dry, the person is thirsty and weak. The skin becomes wrinkled and rough. This is the earliest sign.

Ruru: How do we treat this?

Sushruta: Simple remedies suffice. Drinking water, thin gruel of parched rice, rice gruel, barley flour mixed in water, thin rice soup can restore Rasa quickly, if the digestion is intact. Frequent sips of water of sour, salt, and sweet tastes are enriching.

Ruru: So, if starvation continues, is the Rakta kṣaya next to occur?

Sushruta: Yes. The face becomes pale, exertion leads to easy fatigue, and dizziness occurs. This requires sustained and longer corrective measures.

Ananda: What is given then, Acharya?

Sushruta: Lauha kalpas (iron-based preparations) are useful. Even goat liver helps. These must be given steadily. Rakta is harder to replenish than Rasa.

Ananda: Yes, you told us about liver therapy last time.

Ruru: I guess Māṃsa kṣaya is the next to manifest?

Sushruta: Yes, Māṃsa kṣaya, muscle wasting, and Meda kṣaya, loss of fat, occur almost simultaneously. Sometimes fat loss can occur before muscles grow weak. The limbs grow thin, the person cannot lift weight or walk steadily. One must administer meat soup, goat meat, green gram soup, and strengthen the Agni gradually. Because of Meda kṣaya the body loses its softness, the face appears hollow, buttocks and thorax evidently dry up. Joints, veins and tendons become prominent.

Ruru: You told us that replenishing fat can happen only after muscles are re-built.

Sushruta: Yes, treatment here takes even longer. Replenishing Meda requires Ghṛta (clarified butter), Kṣīra (milk), Taila (oil), and unctuous meats.

Ananda: Even in this case Māṃsa and Meda slightly overlap, right?

Sushruta: Yes, you are right. That is why their depletion and excess can sometimes manifest with similar symptoms. Let us record cases carefully so we may determine precisely how these depletions interplay. We may need to refine this theory if new truths emerge.

Ananda: Next should be Asthi kṣaya then?

Sushruta: Yes, a chronic stage: Asthi kṣaya. The bones ache, teeth loosen, the spine bends, and cracking is heard in the joints and the hairs fall off. This is very difficult to reverse. We use substances that are similar to Asthi to treat it: hard in consistency. Pravāla Bhasma (coral calx), śaṅkha Bhasma (conch shell calx), and also other nourishing oils. But results come only with time, patience, and discipline. Patients are asked to sit under sunlight because the sun hardens the tissues.

Ruru: And Majjā?

Sushruta: When Majjā is depleted, the person grows confused, dull, and may faint. Since all previous dhātus too are depleted, the restoration is still difficult. We give Majjā, Taila, ghee, meat of animals, and also medicated enema, but only the fortunate recover.

Ananda: And what about Śukra?

Sushruta: Well, Śukra. In youth, it is strong. In old age, it declines. When Śukra is lost, the body withers, enthusiasm fades and departs. This is the final dhātu. It is not easily restored. One must turn to Rasāyana (rejuvenative tonics) and Vṛṣya dravyas (drugs that promote sexual health). Internal oleation too can be beneficial. But even these work only when the will of life remains strong.

[He turns to his pupils]

Sushruta: So, remember: in kṣaya (depletion), the order is the same: Rasa first, Śukra last. In upacaya (rebuilding), the deeper the dhātu, the longer it takes to rebuild. Each one must be nourished with proper food, rest, medicines, and time.

[He now concludes]

Sushruta: Do not think that Rasa becomes Rakta, or Māṃsa becomes Meda, or Majjā becomes Śukra, just as milk turns into curd. Each is distinct. The sequence teaches us how to observe, how to treat, and how to think. This is the physician’s path. Should future observations contradict this, we must humbly revise our understanding.

####

Note: No claim of historical accuracy is intended. The remedies mentioned in this chapter are not to be used without the guidance of a qualified physician.

Leave a Reply