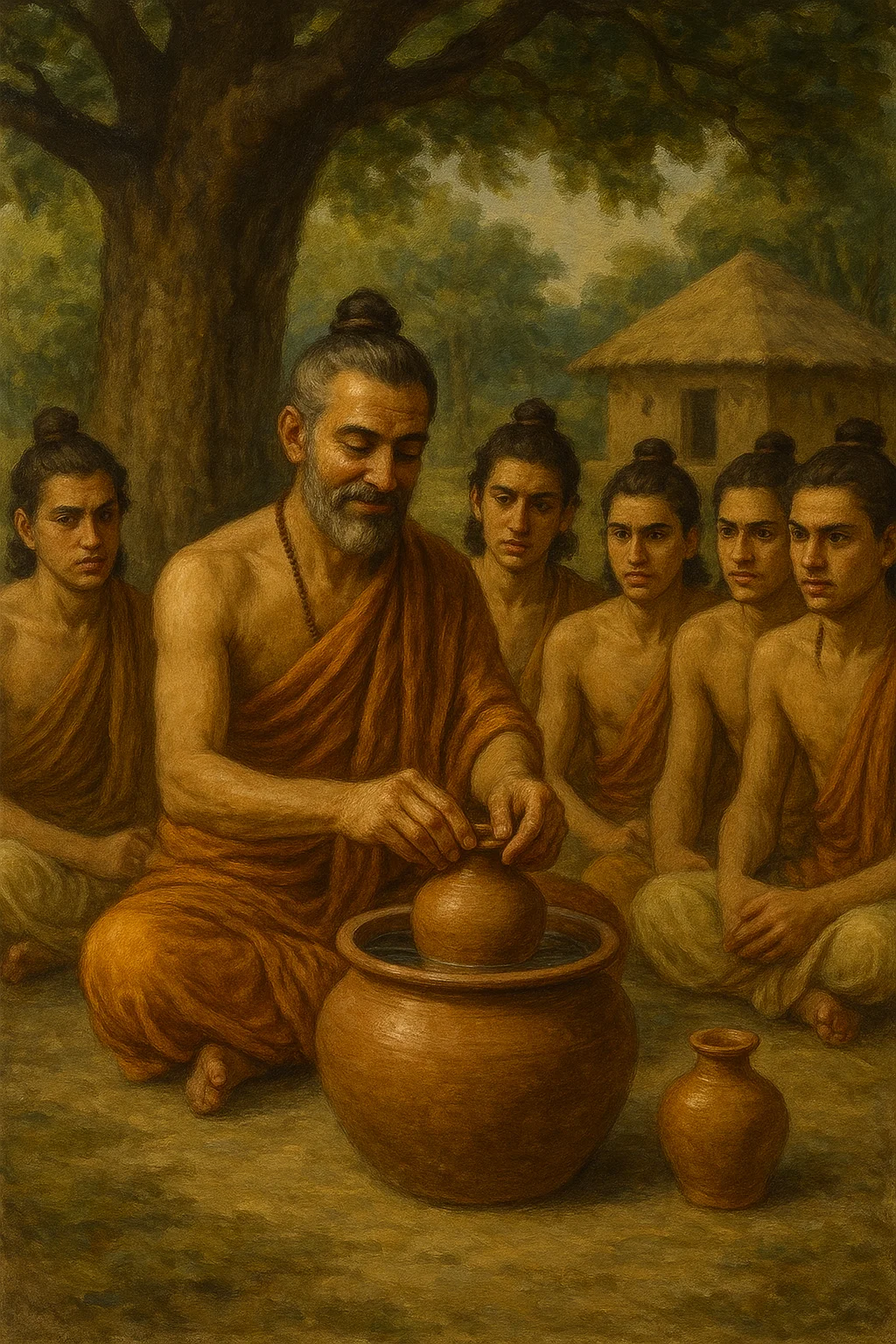

It was early morning. The students sat in silence as their teacher Sushruta arrived, holding a freshly made clay pot. An attendant followed, carrying a larger clay pot, which he filled with water while the smaller one was kept empty. Sushruta seated himself among the students so that he could display the two pots clearly.

Sushruta: Today, we will speak of how our body handles water that we drink. We call it Udaka. Without water one cannot survive. When we are thirsty, we drink water. But all the water we drink doesn’t remain in the body. Some of it is excreted through urine and sweat. Understanding this is essential because it is as essential in diagnosis as it is in health.

[He lowers the smaller pot into the larger one so that it is immersed up to its neck.]

Sushruta: Think of this larger mud pot, filled with water, as the body’s water reservoir. Inside it sits the smaller new mud pot, immersed up to its neck, representing the urinary bladder, Vasti. Just as unseen pores in the pot allow water to collect, in the body, unseen tubules bring urine to the bladder.

Ketana: Water must be seeping outward from the larger pot too. Doesn’t it?

Sushruta: Yes, water seeps outward through the walls of the larger pot and vanishes into the air, just as sweat leaves the skin, or just as the moisture leaves your breath. In winters you can see the water vapour coming out of your mouth when you exhale. In this way, the body regulates water through two routes: inward collection and outward release.

Ketana: But how do we know this? Couldn’t sweat and urine be entirely different things? Why connect them at all?

Sushruta: Observe carefully: that is the dictum. When one drinks much water, the bladder soon fills. When one fasts and drinks none, urine lessens. Hence, there must be a route from the gut to the bladder: not one visible to the eyes or by dissection but this conclusion is drawn through reason and effect. Minute tubules must carry fluid from the site of ingestion to the site of excretion.

Ketana: But that still does not prove the link between sweat and urine.

Sushruta (nodding): Listen to the body. It speaks. In Grīṣma, the summer season, sweat pours freely, and urine becomes scant. In Śiśira, the winter season, sweat is little, and urine flows more. Clearly, the body balances water between different routes of exit. Hence sweat and urine are related. There is no doubt.

Ketana: I understand this. But why should we believe in tubules that we cannot see?

Sushruta: Just as urine and sweat are related, the gut and the bladder too are related. That there are minute tubules joining them is the only conclusion we can draw at present. If there is something more, future knowledge will reveal it.

Ānanda: Why do we feel thirsty?

Sushruta: When the body feels that more Udaka is lost than is to be retained, we feel thirsty. Kloma regulates it. It is located on the right side of the heart, just as the lung is located on the left side of the heart. That is why you see water vapour in the air you exhale.

Ānanda: While dissecting the cadaver we saw another lung on the right side of the heart. Do we call it Kloma?

Sushruta: Some say Kloma is the right lung. Others say it is different. But in my view, since it is slightly different from the left lung in its structure, our teachers identified it as Kloma. That is why on the left side we have Phupphusa, and on the right side we have a similar one, which we call Kloma.

Ānanda: Are the functions of both the organs the same?

Sushruta: Ideally, their functions appear similar. However, there is some difference of opinion here. Since we cannot see how these organs act in living beings, we draw our conclusions by studying dissected cadavers and by comparing them with what we observe in living systems. In future, clearer knowledge may provide a better answer to these questions. Remember, students: what we learn today is what our reason and observation allow us to see. If tomorrow better knowledge appears, we must be ready to receive it.

Ānanda: You taught us earlier that sweat and urine both carry kleda, the moist waste.

Sushruta: True, yet they do so in opposite manners. Sweat expels it onto the skin, moistening it. Urine expels it from within. When one is active, the other is dormant.

[He now lifts the smaller new mud pot and shows it to the students.]

Sushruta: Observe this closely. Such a pot fills not by sudden pouring but by slow seepage. So too is urine collected: not instantly, but gradually, through unseen transfer. In this process the body keeps what is Sāra, the nourishing essence, and rejects what is Kiṭṭa, the useless waste. Urine, therefore, is not raw water, but is waste, processed and expelled by the body’s intelligence.

Ānanda: Ācārya, why is the colour of urine light yellowish? Is there some waste that is yellow in colour?

Sushruta (stirring a pinch of turmeric into the water of the larger pot): Do you recall that the colour of pitta is yellow? Just as this tint pervades the water, so too small amounts of pitta enter the bladder. That is why urine carries a light yellow hue.

Ketana: Oh, is that the reason why urine turns deep yellow in Kāmala, jaundice, and also in Pittaja Jvara?

Sushruta (nodding): Yes. Your reasoning skills are good. In Kāmala, the excess of pitta enters the urine. As you know, Pitta is a waste produced during the transformation of Rakta. When it rises beyond measure, it colours the urine and stool deeply.

Bhadraka: But how do we know that pitta is a waste of Rakta and not something else?

Sushruta: Listen well. Rasa becomes Rakta only through the action of Pitta. We will discuss this in our upcoming lessons. Thus, they share many qualities: heat, sharpness, and colour. Wherever Rakta is disturbed, the signs of Pitta are also seen: yellowing of the skin, staining of urine, splenic enlargement, bleeding and so on. From such repeated observation, our teachers concluded that Pitta is a byproduct released during the transformation of Rakta.

Ketana: In that case, should not the sweat also turn yellow in Kāmala?

Sushruta: In serious cases, the skin itself becomes yellow. How then can one distinguish the colour of the sweat upon it? For this reason, physicians have long looked to the urine as the clearer sign of increased Pitta.

Ānanda: Now I understand why, in Kāmala of the obstructive type, the stools remain white. The Pitta does not reach the bowel!

Sushruta: Precisely! Pitta resides in Yakṛt where it helps in transformation of Rasa into Rakta. Even stools get normal colour because of Pitta.

[Sushruta then takes his students to show two patients who are lying on cots.]

Case 1: The trader with diarrhoea and scanty urine

[Pointing to the weak figure]

This man is a trader who arrived in town after a long travel. Now he has Atisāra, frequent watery stools. His tongue is dry, his limbs weak, and he has passed almost no urine today.

Ānanda: Why is the urine so little?

Sushruta: Because his fluids are escaping through the lower gut. The channels that should send water to the bladder are being bypassed. When distressed, the body prioritizes one route of evacuation over another. As the Kleda, the fluid waste, is being lost through the intestines, little remains to reach the bladder. Therefore, the bladder is not diseased but simply deprived.

Ānanda: Ācārya, what then should be done for such a patient?

Sushruta: When water is spilling through one route, we must gently restore it through another. He must sip frequently sweet-salty water, or a refreshing pānaka. For weak digestion, rice gruel-water or roasted barley flour mixed with water is also suitable. Imagine that such fluids, little by little, refill the larger pot, and from there, some will again reach the smaller one.

Ketana: But will this alone stop his diarrhoea?

Sushruta: For the bowels, one can give Kuṭajārīṣṭa. Kuṭaja is praised for steadying the lower gut and binding the stool.

[He pauses and continues.]

This again proves that water regulation is a coordinated function. When one gate opens wide, others close. Just as Prāṇa Vāyu governs intake, Apāna directs downward elimination, and Samāna Vāyu oversees transformation, movement of water, and also the opening of sweat channels, the balance of these forces ensures that water is distributed and expelled in a proper way.

Case 2: The patient after excessive sudation

[Gesturing to another patient, his garments damp, his face fatigued]

Sushruta: This man was subjected to Sarvāṅga svedana, whole-body fomentation, for his stiffness in all his limbs. The attendants, thinking that more heat meant more relief, prolonged the session beyond measure. Sweat poured in streams, and by the end he complained of thirst, dizziness, and most notably, no urge to pass urine until evening.

Ketana: But Ācārya, can so much fluid be lost in just one sitting?

Sushruta: Certainly. The sveda-vaha srotas, the channels of sweat, can open suddenly and draw out moisture forcefully. The body has only a limited store of udaka (water). When much is expelled through the skin, little remains to be processed into urine. The bladder does not fail from weakness, but from lack of supply.

[He turns to the vessels before him and lifts the larger mud pot.]

Sushruta: Think of this larger mud pot as the body’s total fluid reserve, and the smaller pot as the bladder. If water from the larger pot is poured away upon the ground, how can any be left to seep into the smaller one? Excessive sweating is like such spillage: there is no gradual collection, and thus, no urine.

Bhadraka: And how shall we help him now, Ācārya?

Sushruta: The remedy is twofold: restore and restrain. He must repeatedly sip cool sweet–sour water with a pinch of salt, for what was drained must be replenished, drop by drop. Sweat is salty. Hence you must add a pinch of salt in the water to restore it. At the same time, cooling measures must be applied externally, so that the channels of sweat may close and no further spillage occurs. In this way, balance is regained.

[Replacing the pot gently, he concludes.]

Sushruta: This is why Svedana must be administered with precision, adjusted to season, strength, and constitution. Heat may purify, but when uncontrolled, it drains the very essence it was meant to preserve.

[The students sat in attentive silence as Sushruta replaced the pots beside him.]

Sushruta: Tomorrow is our fortnightly break from studies. Use this pause well. Go into the nearby forests, observe the trees, the herbs, and the flowing streams. Knowledge comes not only from words but also from what the senses gather. Bring back your observations, and we shall speak of them when we meet again.

[The students rose, their minds filled with new questions. With quiet joy they dispersed, already planning their walk into the green world beyond the Gurukula.]

####

Leave a Reply